Club History

‘As Exhilarating as Most Things I Know’[1]: A Short History of Oxford University Cross Country Club

Oxford University Cross Country Club can trace its origins to the mid-19th century, and has played an outsized role in the broader history of cross-country running. The following account provides a brief overview of the club’s long, eventful, and successful history. For reasons of brevity, key junctures have been prioritised at the expense of in-depth, year-by-year detail. Material drawn upon includes contemporary newspaper articles, informal discussions with past and current members of the club, and the invaluable work of Simon Molden, whose illuminating research on the history of the Varsity Match provided a raft of fascinating insights and is well worth a read. I am also grateful to the current club captain, Thomas Renshaw, for proposing the idea that led to this article, as well as for his persistent efforts to procure valuable information about the club.

The Early Years

Reference to what would now be termed cross-country running in Oxford dates back to the mid-19th century. In 1850, Queen Victoria was on the throne, with the Whig, Lord John Russell, as Prime Minister. The year witnessed the Don Pacifico affair and the catastrophic sinking of the RMS Royal Adelaide.[2] More significantly, from our perspective, it also saw undergraduates from Exeter College, Oxford, hold a two-mile ‘foot-grind’ in damp fields at Binsey, west of Oxford. Won by Halifax Wyatt (Exeter), the event marked the first blossoming of organised off-road racing in Oxford, and probably the world.[3] Its success prompted a string of further ‘steeple-chasing’ races in Oxford, including, by 1860, one as part of the university-wide ‘Grand Annual Games’, whose inaugural edition was attended by H.R.H. Prince Edward. Clearly, the future monarch was impressed, donating £10 ‘to a fund for procuring a Challenge Cup, to be held for a year, by the winner of the Steeple Chase’.[4] The early races, though short, covered difficult terrain; and with brooks, thorny hedges, and wired fences amongst the obstacles confronted, certainly lived up to the title of ‘steeple-chasing’.

By 1864, Oxford and Cambridge held their first inter-varsity sports competition in Oxford, with ‘steeple-chasing’ among the sports included.[5] The London Society magazine reported on proceedings, testifying to the authentically ‘cross-country’ nature of the event. It described how the terrain ‘was very rough, the hedges were high, and the lane that had to be crossed was a foot deep in a damp, clayey mixture’.[6] The race was won by Richard Garnett (Trinity, Cambridge), but unfortunately, ‘steeple-chasing’ was dropped from the event schedule at the 1865 competition in Cambridge. Instead, both universities’ committees decided that ‘a flat race of 2 miles was to be substituted for the steeple chase’.[7] Yet, while this marked a temporary setback, the formation of Thames Hare & Hounds in 1868 suggested that cross-country running was not to be an ephemeral presence in the Victorian sporting landscape.[8]

This was confirmed in around 1876, with the establishment of the Oxford University Hare & Hounds. The Field reported that a ‘hare and hounds club has been started in Oxford, and has hitherto been very successful’.[9] Albert Goodwin (Jesus) was elected the club’s first president, and before long, large numbers were involved. Officially, O.U.H.H.C. was a branch of our sister-club, Oxford University Athletics Club, and was financially dependent upon it. Club runs were organised on a weekly basis and always set off from an Oxford pub, for example, the King’s Arms on 9 May 1876.[10]From there, the ‘hares’ would depart first, leaving a paper trail that the ‘hounds’, who usually left around ten minutes later, would follow. Routes took in locations familiar to subsequent generations of club members, such as Bagley, Shotover, and Wytham. Less familiar, perhaps, were some of the challenges encountered by the runners. Alongside the prospect of getting lost or succumbing to fatigue, athletes faced ‘shouts of righteous indignation on the part of the rusties at seeing their crops overrun’.[11] On one occasion, in October 1876, ‘the hounds were suddenly stopped by a fierce looking individual with a gun, who threatened to shoot anyone who chased the two noble gents [hares], whose health, it is said, he had been allowed to drink’.[12] Thankfully, the hounds escaped this testy encounter through a gap in a hedge and continued their chase. Such anecdotes convey the wildness and excitement of these runs for the participants involved, which obviously held allure, as the club enjoyed an explosive early spurt in membership.

1898 Varsity Match Start-line

What was lacking, however, was an inter-varsity rivalry, potentially contributing to the club’s waning popularity in 1878. This was addressed when Cambridge Hare & Hounds held their first run in February 1880.[13] By 2 December of that year, the first Varsity Match had been scheduled, setting off from the Royal Oak on the Woodstock Road, Oxford. The five-man Oxford team included Messrs. Edward and Payne of University College, Grinstead and Hernaman of Keble, and Hewetson of Worcester. Following the traditional racing format, Oxford eventually emerged victorious, by 23 points to 32, and with Charles Grinstead claiming the individual title.[14] This, however, was only after two Cambridge runners got lost, highlighting the essentially haphazard and informal nature of early competition.

Growth and formalisation

In subsequent decades, the Varsity Match established itself as a regular fixture in the sporting calendar. From 1881 to 1887, Cambridge dominated,[15] with Oxford suffering, amongst other things, from a tetchy relationship with O.U.A.C., the latter unwilling to relinquish athletes for fear that long and difficult cross-country runs would dampen athletes’ speed. Difficulties were such that by 1884, only eight runners showed up to the club’s trial race.[16] Thankfully, matters soon improved, aided by the leadership of William Pollack Hill (Keble). In 1888, Oxford tasted Varsity victory once more, inaugurating a fresh era of competition.

There were other notable developments (and ultimately non-developments) in this period. One was a shift in venue for the Varsity Match. With both Oxford and Cambridge teams dissatisfied about the extent of home advantage, it was agreed to hold the 1890 edition in Roehampton, hosted by Thames H&H. Unfortunately, several runners ended up lost.[17] But in 1896, the event returned to Roehampton, where it would remain until 1925.[18] The late-1890s also saw renewed debates about Oxford University H&H’s relationship with its sister-club, O.U.A.C.. In 1898, the Abergavenny Chronicle noted that ‘cross-country running on the part of the Oxford University has been at so low an ebb in recent years’.[19] This prompted proposals, ultimately left unimplemented, that Oxford cross-country runners form themselves into a separate club, rather than remaining merely a branch of athletics.[20]

1908 Varsity Match Start-line

This ‘low ebb’ receded, with a talented crop of runners – including, from the American Warren Schutt onwards, several Rhodes Scholars – emerging in the early-20th century.[21] As well as competition against Cambridge, the club also increasingly participated in meets against ‘plebeian’ cross-country clubs. These included Thames H&H, the United Hospitals H&H, South London Harriers, Blackheath Harriers, and Ranelagh Harriers. Increasing standards, greater engagement with the broader running fraternity, and the general classness-ness of cross-country running, brought broader press coverage of the club’s activities. Reflecting this, one correspondent for The Times remarked in 1909 that ‘formerly little interest was felt in cross-country running at Oxford and Cambridge…To-day things are very different’.[22] Indeed, by late-1909, the club’s victory against Derby and County A.C. was covered as far afield as the Lisburn Standard in County Antrim.[23] Such competitions were abruptly, and tragically, terminated by the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914.

Between the Wars

After the harrowing disruption of conflict, runners were keen to rekindle pre-war habits. The Varsity Match returned in 1919, won by Magdalen’s Evelyn Montague, who was also victorious in 1920.[24] Yet, this was also an era of significant developments for the club. First, 1919 proved the last in which cross-country runners competed under the O.U.H.H.C. banner.[25] For the next seven decades, they bore the crest of O.U.A.C., a marker of the sport’s decisive acceptance by athletics, and diminishing their sometimes difficult past relations. 1919 also saw the appointment of Alfred Shrubb as the club’s first coach. Yet, despite his running prowess – setting 28 world records over the course of his career – he was dismissed as a ‘useless’ coach by committee members in 1927.[26]

Oxford’s runners also joined their Cambridge counterparts to form an Oxbridge team to compete against visiting runners from Cornell University, then America’s leading university for athletics, in 1920. The event drew large crowds and was ultimately won by Oxbridge, but only by the narrow margin of 26-29.[27] Oxford also branched out to inter-varsity meets against Trinity College, Dublin, defeating the latter by the decisive margin of 15-40 in 1924.[28] As well as this, the Varsity Match itself underwent innovations: first, owing to encroaching development, the venue was moved from Roehampton to Horton Kirby in 1926, where it would remain until 1938.[29] Second, from 1937, a sixth man was included in scoring.[30]

1929 Varsity Match

The club, moreover, was increasingly shaped by deep-seated social changes impacting on the city and university of Oxford. The former underwent rapid expansion during the interwar period, most lucidly reflected in car factories at Cowley.[31] From the cross-country perspective, this unfortunately resulted in the swallowing up of large tracts of countryside, especially towards Shotover, replaced with tarmac and concrete. From thenceforth, off-road running in Oxford would be less simple. The university’s student body, meanwhile, was becoming both larger and less elite. Balliol College, for instance, went from 53 entrants (19 from Eton) in 1906, to 104 (14 from Eton) in 1939.[32] This contributed to a larger cross-country membership, which, by the 1930s, resulted in the formation of a men’s seconds team, later named the ‘Tortoises’, which counted the future Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, within its ranks.[33] This proved a precursor to further increases in the club’s inclusivity during the 20th century.

Post-War Rebound and Full-Blue Status

The Second World War augured further disruption, while prompting a return to the practice of alternating venues between Oxford and Cambridge for the (now unofficial) Varsity Match.[34] After the war’s conclusion, Varsity returned to Roehampton. Several route variations were trialled, but these were generally contained almost entirely within Wimbledon Common. Beyond this, the immediate post-war years brought other important developments. In 1947, Oxford runner, Peter Curry (Oriel) led the Varsity Race, but allowed his teammates – Messrs. Pollard (Pembroke), Ridding (Oriel), and Green (Magdalen) – to join him.[35] All crossed the finish line together, causing a headache for the Blues Committee which ultimately resulted in all four receiving full Blues, more than had been given in the past, and setting a precedent that bolstered the sport’s quest for full Blue status later on. In 1948, meanwhile, the Varsity scoring system was changed to its present arrangement of eight runners, with six to score.[36]

Roger Bannister winning the 1949 Varsity Match

Yet, perhaps most significantly, this era saw the emergence of some of the most talented members in the club’s history. Most famously, there was Roger Bannister (Exeter). First appearing as a ‘Tortoise’ in 1946 (proving how this team aided athlete progression and development), he finished joint-second in the 1948 Varsity Match, before emerging victorious a year later.[37] Bannister, of course, would go on to break the four-minute mile for the first time at Iffley Road track in 1954, cementing his status as Oxford’s most famous sportsperson. Yet, Bannister was only one of a host of talented athletes representing the club in this period. Another was Chris Chataway (Magdalen), who won three successive Varsity Races between 1950 and 1952,[38] before going on to set a 5000m world record of 13 minutes 51.6 seconds in London in 1954; the latter resulting in his receipt of the inaugural BBC Sports Personality of the Year Award. Such athletes surely helped shift the impression – acknowledged by 1950-51 O.U.A.C. captain, Nick Stacey (St. Edmund Hall) – that cross-country, despite its popularity, ‘seems to get less publicity and lacks glamour’.[39]

1967 Varsity Match in the snow

In the 1960s and 1970s, university-level sport faced a string of challenges. In a more meritocratic post-war society, there was greater pressure to attain a good degree, while university dons had grown more critical of time spent by students on sport.[40] Cross-country – with its emphasis on restraint, self-discipline, and, ultimately suffering – also sat less comfortably within a youth culture summarised by the epithet of ‘sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll’. Nevertheless, perhaps aided by the inspiring calibre of athletes in the early-1950s, the club remained on a strong footing. In 1951, the third team – later known as the ‘Snails’ – competed in the Varsity Match for the first time, joined by fourths in 1958, and fifths in 1966.[41] Most significantly, the first ladies’ Varsity Match was held (unofficially) in 1975, resulting in a 7-14 Oxford victory.[42]

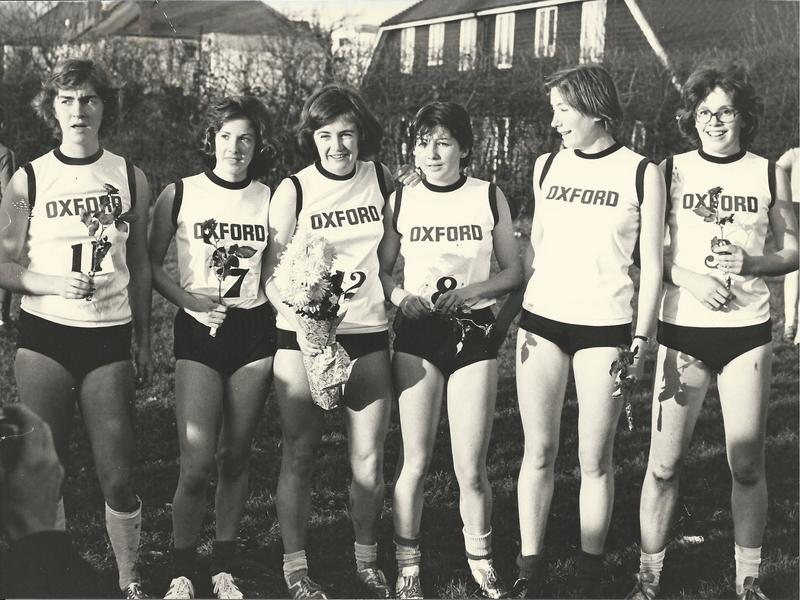

The 1975 Ladies' Team prior to the first unofficial Varsity Match - Hudson, Mackenzie, Meunier, Wightman, Halfpenny

The first official ladies’ race followed one year later at Roehampton, won individually by Lynne Wightman (Lady Margaret Hall), and by Oxford with an emphatic 10-34 margin.[43] By 1983, a ladies’ second team (the ‘Turtles’) began competition, alongside a non-selected race in 1987.[44] This expansion in teams provided younger or less experienced athletes with the opportunity to gain cherished Varsity memories, acted as a stepping-stone for some to go on to Blues teams, and cemented the affinity of many others to the university.

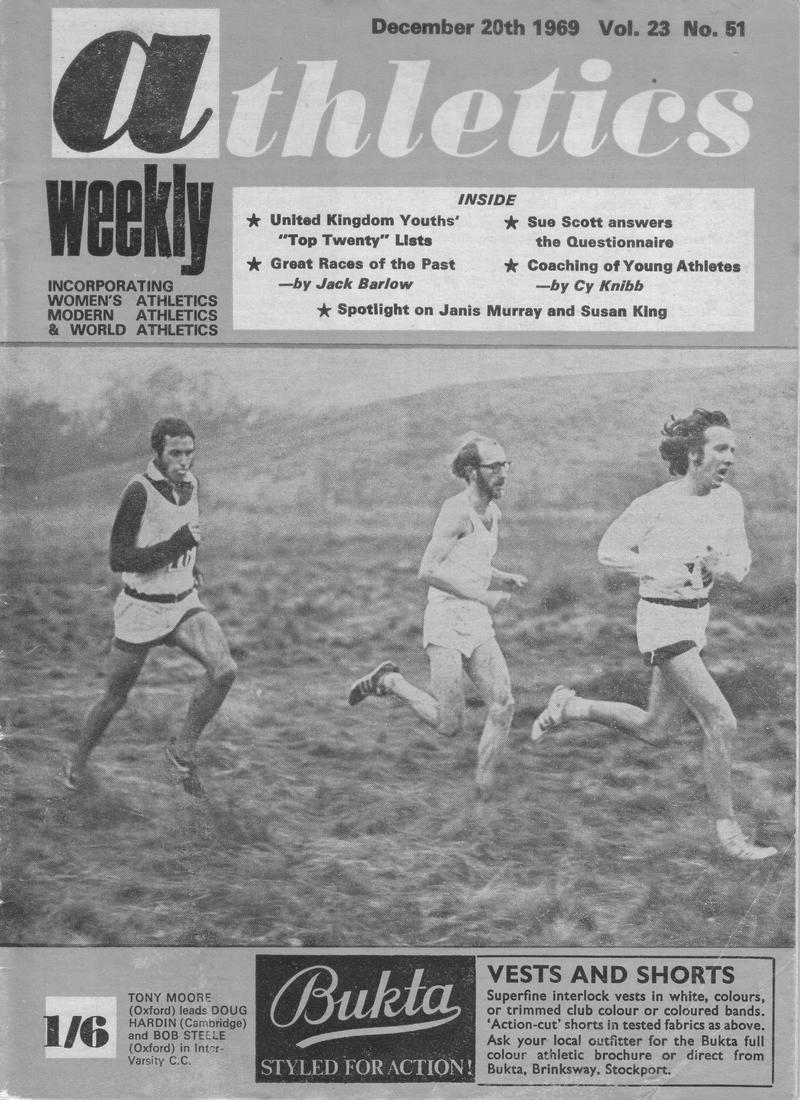

1969 Varsity Match on Athletics Weekly cover - Steele, Hardin, Moore

By the 1970s, leading Oxford runners were completing regular twice-a-day training – a far cry from training schedules in the club’s early years – and enjoyed an era of dominance vis-à-vis their Cambridge rivals. This helped affect, in 1978, another watershed moment in the club’s history, when cross-country running was at last awarded full-blue status by the Blues Committee.[45] This capped a long journey from the days when the days when it was feared that this irksome sport would undermine the speed of Oxford’s prime runners.

1976 Ladies' Varsity Match - Stead, Grand, Wightman, Halfpenny, Skrine, Hudson

Recent Times

In recent decades, cross-country has remained an integral and successful part of the Oxford University sporting landscape. In 1990, under the captaincy of Chris Daniels and reflecting its self-confidence, the club reasserted its distinct identity, competing under the mantle of Oxford University Cross Country Club, with O.U.C.C.C. proudly emblazoned on club vests.[46] As well as the Varsity Match, the British University Cross Country Championships also rose in competitive importance, following the first event at Nottingham in 1964. Oxford remained consistently towards the business-end of proceedings. First hosting the event in 1998, our women emerged victorious in 2000.[47] More recently, 2019 saw our men’s team place 3rd out of 50 teams in the A race, and our women’s team come 4th out of 189 teams in their race.[48]

1998 Varsity Match

Conclusion

Cross-country running at Oxford thus boasts a long and illustrious heritage. From Sydney Sarel (Keble) at London in 1908, to Mara Yamauchi at Beijing in 2008 and London in 2012, numerous Olympians have passed through the club ranks.[49] Yet, alongside this performance pedigree, cross-country running at Oxford has repeatedly evinced a spirit of camaraderie, a love of the outdoors, and a growing breadth of participation. Indeed, the latter qualities have often contributed to competitive success, most recently in the 2021 Varsity Match, when Oxford emerged victorious from six of the seven races.

Over the course of its history, one quickly gleans that O.U.C.C.C. enjoys its strong position today thanks to the diligent efforts – both on and off the race-course – of generations of athletes, passionate about their sport and their clubmates. Some received mention by-name in this article, but vastly more did not. Yet, to all we are indebted. By continued effort and enthusiasm, current and future club members can add further chapters to this ongoing story.

Jared Martin

(Merton College; Men’s Vice-Captain 2022-23)

More On The Women

The oldest cross country history concerns only the men so it can be all too easy to overlook the rich history behind half of the club we are today. Far from being forgotten, we should celebrate the tales of the women’s side that document its ascension from tentative origins to the dominant force it is today.

The first Ladies’ Athletics Varsity match was unofficially held in 1975 after two post-war decades of gradually increasing female intakes at both Universities. That Autumn, Oxford, led by their first Ladies' Captain, started to make plans to host a similar Varsity Match for Cross Country in conjunction with IInds-Vths Gentlemen’s Matches. A major milestone in Varsity Cross Country history, the Ladies' Race was a small affair with only three runners representing each of the Universities. Oxford, led by C. J. Meunier of St Hugh’s, won this inaugural event by 7 points on home turf at Shotover.

1992 Ladies' Varsity Match

The continuing growth of women’s cross country saw the first Official Ladies’ University Cross-Country Race take place the following year, this time alongside the Gentlemen’s Blues match at Roehampton. Despite some reluctance from Thames, which was still an all-male Club, to take on its organisation, John Bryant agreed to devise a 2.8-mile course over which the women would compete directly before the Gentlemen’s race began. As mentioned above, the 1976 winner, and previous season’s Oxford Ladies’ Captain was Lynne Wightman of Lady Margaret Hall who led the dark blues to a dominant 24 point victory over Cambridge, this time with six runners competing for each university.

Since then the Ladies’ Match has continued to take place immediately before the Gentlemen’s Blues although the course and scoring has varied over the years. Until 2013, the top four from each team of six counted and this was expanded to five from teams of seven in 2014. 2018 saw the scoring align with the men for the first time, as each university fielded a team of eight with the first six scoring and the remaining runner’s places counting. The original 2.8-mile course remained until 1991 but over the years that followed it was gradually increased until today’s 4-mile course was settled on in 2000. Oxford Women enjoyed a period of dominance in the 1990s with a record 9 consecutive victories between 1993 and 2001. Within this time OUCCC elected its first female Club Captain, J. Martin of LMH in 1996. Since then 7 more women have taken up the position.

As well as the Ladies’ Blues Matches, the continuing growth in the women’s teams led to the introduction of the IInds race in 1983 at Shotover, and only four years later the Ladies’ IIIrds race was included in the Varsity programme for the first time. Similar growth across the country has seen the BUCS XC Championships add the short course B race for the women in 2019 to bring the format in line with the men’s. There is still discrepancy in race distances between men and women in many league and championship races across the country, with Varsity and BUCS no different. This remains a contentious issue and surely will continue to be debated. No matter, something that cannot be questioned is the strength and depth of Oxford Women’s cross country in recent times. With record numbers taking part in Cuppers’ in 2021 and a 3-0 victory at Varsity that same year, the women’s side of OUCCC is in a great place and we have every confidence it will remain this way for many years to come.

Charlotte Buckley

(Oriel College; Ladies' Captain 2022-23)

Links to Further Reading:

http://www.thameshareandhounds.org.uk/varsity-match/

https://www.ouac.org/history-club

https://cuhh.soc.srcf.net/about/history/varsityhistory/

[1] Simon Molden, Hares, Hounds and Blues: A History of the University Cross-Country Race, 1880-2019 [Second Edition] (2020), p.80.

[2] David Cannadine, Victorious Century: The United Kingdom, 1800-1906 (London: Penguin, 2017), pp.246-7.

[3] Simon Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, pp.3-4.

[4] Ibid, p.4.

[5] ‘Oxford and Cambridge Athletic Sports’, Bell’s Life in London, 12 March 1864.

[6] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.6.

[7] ‘Oxford University Athletic Sports 1865 Committee’, O.U.A.C. Minute-Book 1860-69, 1865.

[8] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.7.

[9] Ibid, p.13.

[10] ‘The Oxford University Hare and Hounds Club’, Oxfordshire Weekly News, 17 May 1876, p.3.

[11] Ibid.

[12] ‘Oxford University Hare and Hounds Club’, Oxford Times, 28 October 1876, p.2.

[13] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.19.

[14] Ibid, pp.29-30.

[15] Simon Molden, The University Cross-Country Race: A Complete Record, pp.2-6.

[16] Molden, 2020, p.41

[17] Ibid, p.86.

[18] Ibid, p.100.

[19] ‘Current Sport’, Abergavenny Chronicle, 11 November 1898, p.7.

[20] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.111.

[21] Ibid, p.128.

[22] Ibid, p.129.

[23] ‘Sports and Pastimes’, Lisburn Standard, 27 November 1909, p.6.

[24] Molden, Complete Record, p.20.

[25] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.157.

[26] Ibid, p.160.

[27] Ibid, p.177.

[28] ‘Athletics’, Sport [Dublin], 23 February 1924, p.14.

[29] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.180.

[30] Ibid, p.195.

[31] Peter Clarke, Hope and Glory: Britain, 1900-2000 [Second Edition] (London: Penguin, 2004), p.178.

[32] Albert Henry Halsey, ‘Oxford and the British Universities’, in Brian Harrison ed. The History of the University of Oxford: Volume VIII: The Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), p.586.

[33] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.209.

[34] Ibid, p.217.

[35] Ibid, p.230.

[36] Ibid, p.231.

[37] Molden, Complete Record, p.35.

[38] Ibid, pp.36-37.

[39] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.263.

[40] David John Wenden, ‘Sport’, in Brian Harrison ed. The History of the University of Oxford: Volume VIII: The Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), p.519.

[41] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.213.

[42] Molden, Complete Record, pp.73.

[43] Ibid, p.74.

[44] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, p.213.

[45] Ibid, p.278.

[46] Ibid, p.294.

[47] Ibid, p.299.

[48] ‘BUCS Cross Country Championships 2019’, BUCS Cross Country Championships, https://dbmaxresults.co.uk/results.aspx?CId=16421&RId=2241.

[49] Molden, Hares, Hounds, Blues, pp.320-324.